July 2019

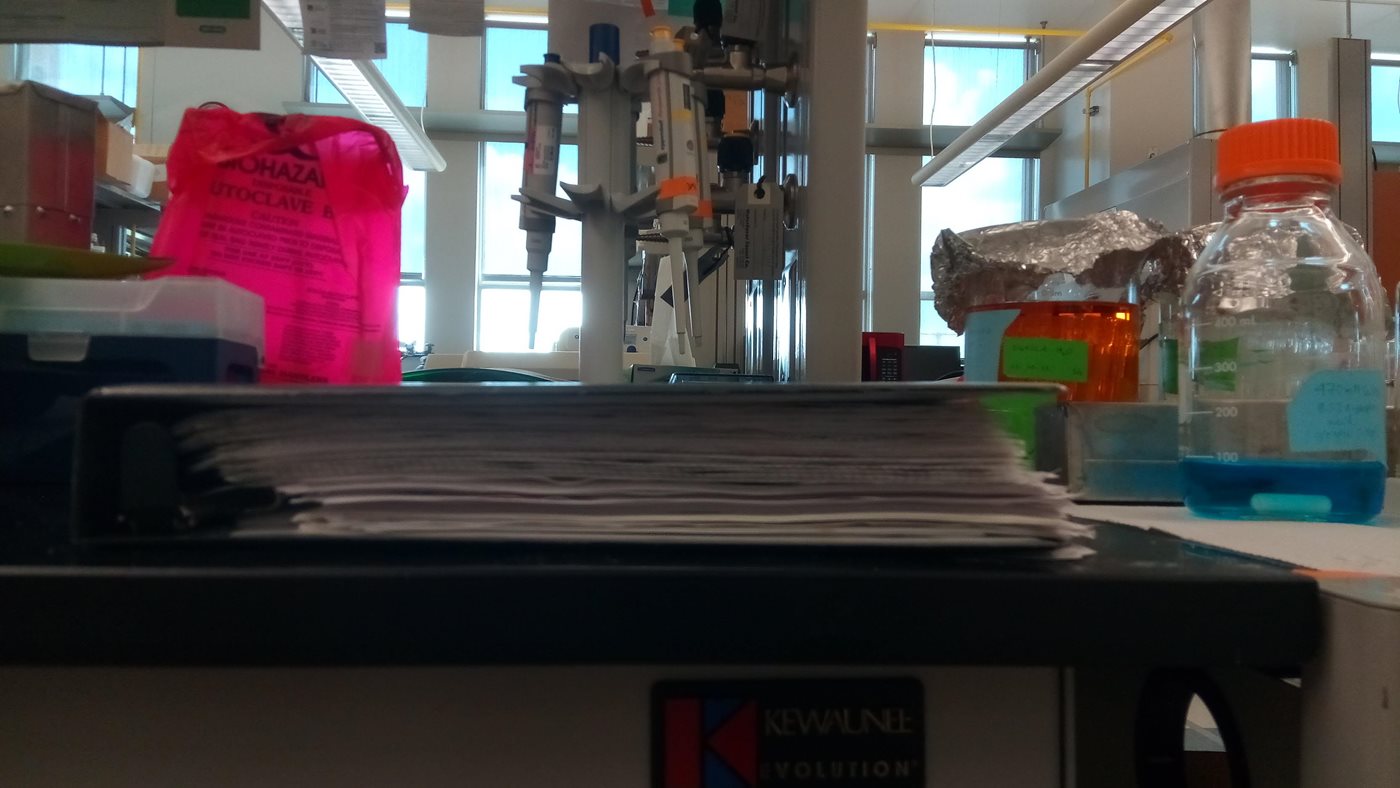

Some people in a lab can do something one time and remember everything in perfect succession including specific numbers for 100 different steps. That is definitely not me. One key thing about science is reproducibility and if you can’t remember how you did something the first time, chances are you will not be able to reproduce it. Therefore, making protocols cuts out the middle man so that you can do the same experiment time and time again (which is the definition of graduate school). Follow my protocol below and hopefully your biology is as stable as the protocols.

How to make protocols

- Title, your name, the date, and the original paper(s) the protocol is adapted from

- You want your name on this protocol because 10 lab rats can do the same protocol in slightly different ways. As you will see, sharing these protocols will change them as new students join, or current lab rats lose their copy. Be the expert on your own protocol and help those protocol-less animals out.

- The date is important to indicate if somebody should ask if there are any changes to the protocol. A protocol that is 10 years old might have a shorter way to do it. A protocol written 2 weeks ago might still be in the process of optimization.

- The original papers will save you in more ways than one. Having this on the protocol will keep the reference around for the methods section of your paper. It will also tell others what the changes are to the original protocol and how the results could differ.

- Introduction

- You won’t always see this on a protocol, but it can be very helpful for distinguishing similar protocols or giving the information for what this protocol is actually used for. For example, my protocol called ‘How to use the AKTA system’ is really how to use a machine for gel filtration to isolate my special protein from other useless ones. This is relevant information to put in the introduction.

- Materials

- Put the exact materials you are using and how much you will need. This includes machine names and models because as time goes on, the protocol will not be standardized for the equipment in the lab. This will help the methods section of your paper in the long-run because more and more journals are asking for this specific information. Having the amount of each material helps with quickly looking before you begin the experiment to ensure that all the materials are available and nobody left an empty bottle in the cabinet.

- Step-by-Step

- Write every step as you do it, sometimes even down to how to hold the tube. Each step gets its own number, this helps when your feeling tired and not reading well. For things to watch out for, indenting below the step helps. In this area, putting observations also helps. If it should be yellow but your product is pink, you would know something went wrong. When making the protocol, you will think to yourself, ‘I will remember this surely,’ but after 4 years away from this protocol, you will thank yourself for putting in this valuable information.

- Conclusion

- This could include what experiment usually happens after this one. For example, if you made something like a new yeast strain, you will want to characterize it to be sure you made the correct thing. Also, you might want to put yields here so that you know how much you expect to get because usually when you make something, it is then used for something else.

People out there who are cooking have recipes. Scientists have protocols. Make your protocol good not only for future you but also for the good of the lab. Other than experiment protocols, I suggest making protocols for things like writing, coding, or even oral presentations. I hope this protocols inspires more protocols and we live in a more reproducible world.

---Donna Iadarola

Donna Iadarola is a Doctoral student in the College of Agriculture