February 2024

“What are you asking me?”: On Privacy in the Academy

By Delaney Couri

As of a few weeks ago, I have officially begun working on my dissertation. This dissertation is the only thing standing in the way of me and graduation, and so for the next 16 months it will be pretty much the only school-related topic I plan to think about.

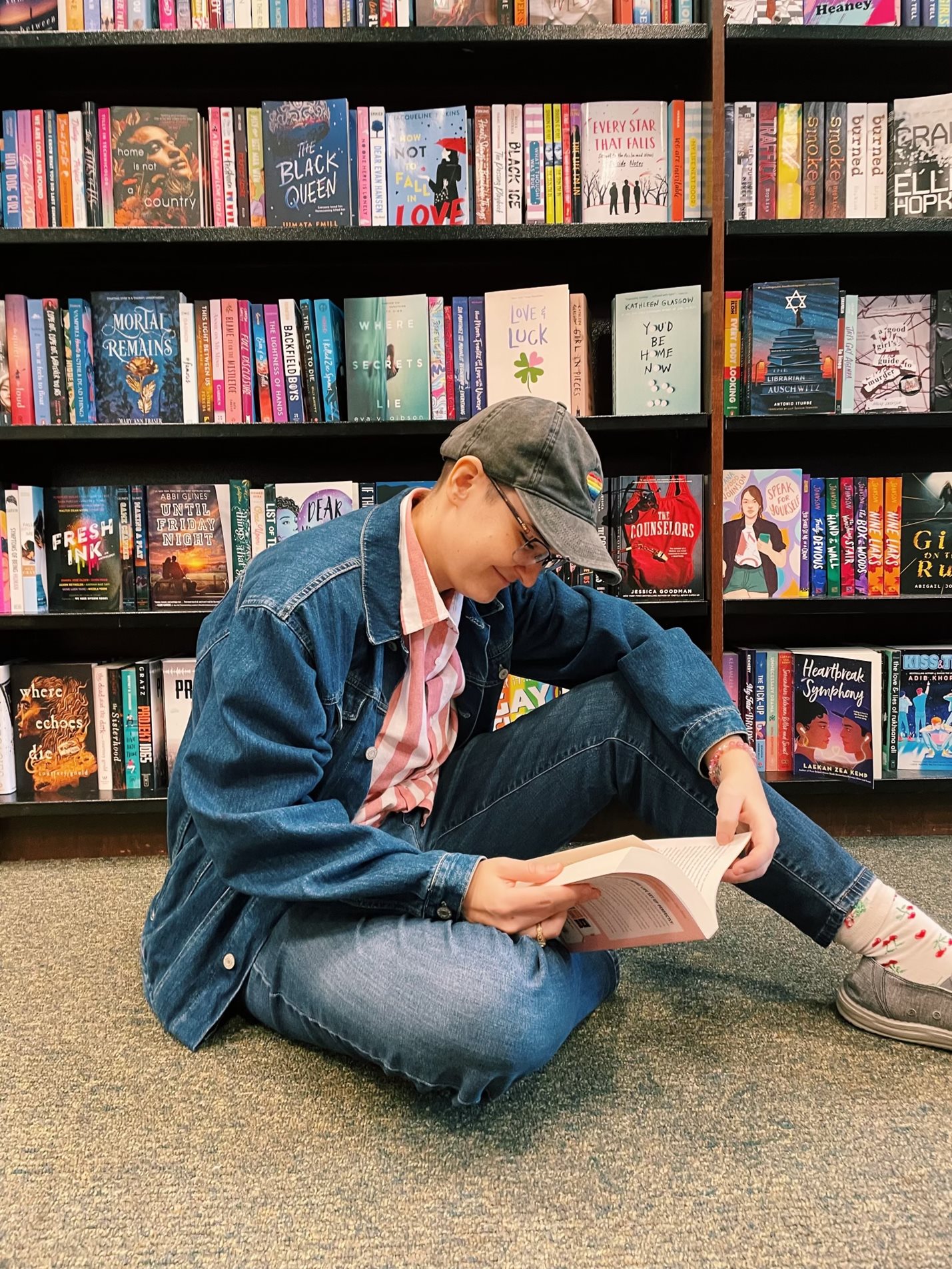

The first step in my dissertation writing process has been reading. It’s ironic that a doctorate is framed and imagined as a degree given out to those who do research writing when I think the core of a research degree is based more in reading than anything else. For me, this reading has thus far been self-directed. I find a topic, discuss its relevance with my advisor, then she sends me out into the world to learn as much as I can about said topic. This means digging into years and years worth of journal articles, books, conference proceedings, and anything else I can get my hands on to help me understand both the conversation I am entering into and the spaces where conversations are yet to be fully developed. In other words, what my writing will contribute to and how it will contribute to this area.

This sounds fairly easy on the surface. As I jokingly said to my advisor, “So, my homework is to read books and watch television? Okay, sure, I can do that.” But I think I underestimated just how much of a toll this reading would have on me— specifically in this sociocultural historical moment.

You see, there have been a lot of conversations happening around me lately about the topics I am studying, who is studying them, and why that matters. It turns out, studying (and teaching) about issues of gender, sexuality, race, religion, nationality, and entertainment media are fraught with significance far beyond what can be seen on the page. And the problem is, in this age of social media productions and civilian journalism, everyone seems to think that they have a right to what everyone else thinks, believes, and feels— and a right to everyone’s personal identity.

This line of logic, that we have a right to invade other people's privacy, seems outwardly to be anti-American in its logic. America is the land of the free and the home of the brave, right? Doesn’t this lead to an individualistic mindset which implies that identity and personhood are private and housed in an individual rather than in collectives and groups?

It may seem so at first, but the more I read, talk, and think about it, it seems that our desire to be free somehow makes us think that we also have the right to invade the minds of others for our own comfort and safety. In other words, our freedom of privacy ends where another person’s feelings begin. This right to know other people is both built into and protected by law. The Freedom of Information Act literally allows individuals to ask and access almost any information they want on citizens working in a publicly funded sector, whereas FERPA (Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act) supposedly is in place to protect student information, but also serves as a legal way for certain parties to gain access to records that are otherwise closed off.

While I argue that this culture of surveillance is built into the standard traditional American ethos, it is also fueled by the newer obsession with both celebrity and authenticity. This appears most commonly in calls for accountability regarding media portrayals of individuals of marginalized groups. For instance, white writers writing Black characters or straight actors portraying queer characters.

These questions and concerns about legitimacy of mediated writings and portrayals are valid and often arguably morally good. There is a history of misrepresentation due to misunderstanding or outright discrimination. So, in these instances, someone from a marginalized group watching a movie or television show and noticing the portrayals seem stereotypical who then goes to search out the writer’s credentials or identity can be a liberatory act. Calling on individuals to be accountable to the groups they are writing about (presuming they are not a part of them) is important.

Where this gets dicey is when searching out identity becomes attached solely to an individual's desire to understand someone’s credentials or qualifications. In other words, when the desire to know becomes the right to know other people’s private affiliations.

This brings me to the title of this blog. As someone who identifies as queer and non-binary, a lot of the reading I have been doing lately applies directly to my life. Because of this, I sometimes get curious about the positionality (identity) of the person writing it. In one such instance of curiosity, I wandered into my advisor's office to ask her why a certain individual was writing about lesbians.

She looked at me, long and hard, and in a somewhat incredulous tone just said, “What are you asking me?”

I instantly froze.

“What AM I asking you?” I said back.

At that moment, I realized that my question, though seemingly innocent, was potentially outing a writer. I wanted to know why someone was writing about the community I belong to, which feels reasonable, but in my quest for that knowledge I blatantly stepped on personal boundaries because of my supposed “right” to know where someone else is coming from in their writing.

In this blog, I self-disclosed my queer identity. If anyone reading my writing someday about the LGBTQ+ community wants to know what my inversement is, they will see that it is one of identity. But just because I am openly queer does not mean that everyone is, and no one has a right to force someone out of the closet just because they think their writing or portrayal of a queer person or character is not well done.

This also holds for individuals writing about groups outside of their own. Sure, I may be skeptical if a straight person is writing about lesbian experience, but their credentials may be academic rather than lived. Either way, this does not mean that they don’t have credentials. Or maybe their credentials come from having a queer sibling who they discussed their writing with. Though it does matter as a way to combat stereotypes and inaccurate portrayals of marginalized groups, the lack of an outright identity alignment does not foreclose the possibility of thoughtful, encouraging, well-written texts.

In 16 months, I will have hopefully finished a dissertation about queer religious characters and the way their identities are depicted on screen. Anyone is welcome to read my writing and I am always open to suggestions and calls for accountability when I make a misstep. What I am not okay with is the idea that I have to disclose every facet of my personal identity to make others comfortable or get them to trust in the writing that I am doing.

Hopefully, by the time I am finished, my writing will speak for itself. And hopefully I can learn to give up my selfish desire to know intimate details about others and let their writing speak for itself, too.